Leg Day Anatomy: A Lifter’s Guide to What Moves the Weight

Most people treat leg training with a broad brush. You squat, you press, maybe you throw in a few curls, and you call it a day. But if you have ever wondered why your knees ache after running or why your squat numbers have plateaued despite consistent effort, the answer usually lies in your anatomy. Understanding the specific muscle groups in your legs is the difference between simply moving weight and actually training the body for performance and longevity.

The lower body is a complex system of levers and pulleys. It isn't just about the thighs and calves; it is a kinetic chain where every link affects the others. When you break down the anatomy, you realize that "leg day" is actually a misnomer for managing a massive percentage of your body's total muscle mass.

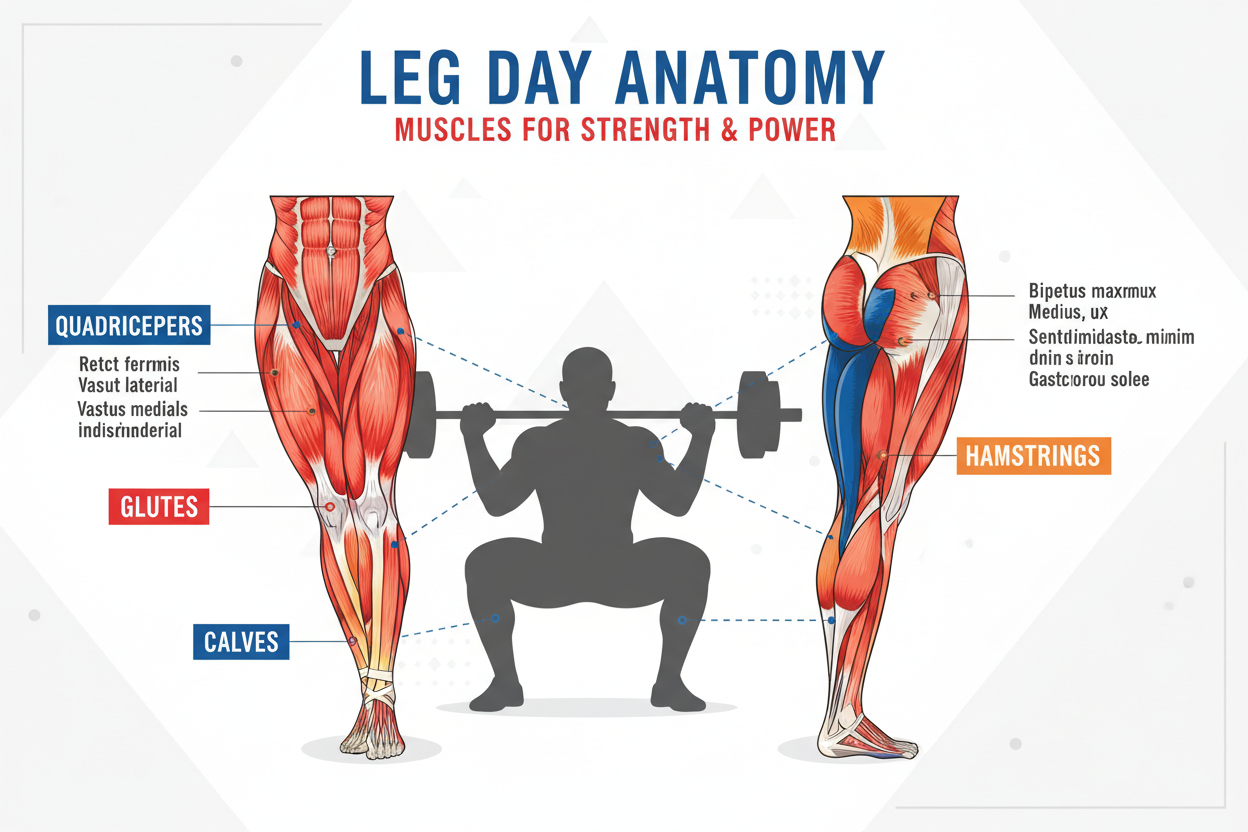

The Quadriceps: The Powerhouse of the Front

The most visible muscles on the front of the thigh are the quadriceps. As the name implies, this group consists of four distinct heads. The vastus lateralis sits on the outside and gives the thigh its width, while the vastus medialis (often called the teardrop muscle) stabilizes the knee joint on the inside. The vastus intermedius runs deep down the center, buried under the rectus femoris.

The rectus femoris is unique here. unlike its three brothers, which only cross the knee joint to extend the leg, the rectus femoris crosses the hip as well. This means it plays a dual role: extending the knee and flexing the hip. If you only perform leg extensions, you are missing out on the full function of this muscle group. To fully engage the quads, you need movements that challenge knee extension while the hip is in various positions.

The Posterior Chain: Hamstrings and Glutes

Turn the leg around, and you find the engine of your athleticism. The hamstrings are not just a single muscle but a trio: the biceps femoris, semitendinosus, and semimembranosus. These muscles are the direct antagonists to the quads. While the quads extend the knee, the hamstrings flex it. However, their most critical function for power is hip extension.

Many lifters suffer from "quad dominance," where the front of the leg overpowers the back. This imbalance is a recipe for ACL injuries and lower back pain. Proper training here requires hitting both functions. You need leg curls to address knee flexion, but you also need hip-hinge movements like Romanian Deadlifts to train the hip extension capabilities of the hamstrings.

While often categorized separately, the glutes function inextricably with the upper leg muscles. The gluteus maximus is the primary driver of hip extension, working in concert with the hamstrings during squats and lunges. Neglecting the glutes forces the hamstrings to take over the entire load, often leading to strains.

The Adductors and Abductors: The Forgotten Stabilizers

If you have ever felt your knees caving inward during a heavy squat, your issue might not be your quads at all. It is likely your inner and outer thigh muscles failing to stabilize the femur.

The adductor group (inner thigh) brings the legs together. These muscles are massive and contribute significantly to squat strength out of the bottom of the hole (the lowest point of the lift). Conversely, the abductors (including the gluteus medius and tensor fasciae latae) on the outer hip pull the leg away from the midline. They prevent the knee from collapsing inward. Strong legs are useless if they cannot track straight, and these stabilizer groups are the guardrails that keep your movement efficient.

My Experience with Imbalanced Training

Early in my lifting career, I was obsessed with the mirror muscles. I hammered leg extensions and leg presses, building decent-sized quads, but I completely ignored the stabilizers and the posterior chain. I thought I was strong until I developed a nagging pain in the front of my knee—patellar tendonitis. It got so bad I couldn't walk down stairs without wincing.

A physical therapist pointed out that my vastus medialis was weak, and my glutes were essentially dormant. My quads were pulling on my kneecap unevenly because the supporting cast wasn't doing its job. I had to drop the heavy weights and focus on single-leg split squats and hip thrusts. It took three months to fix, but once those stabilizers caught up, my knee pain vanished, and my main lifts shot up by 40 pounds. It was a hard lesson: you cannot hide weak links in the lower body.

Below the Knee: More Than Just Calves

The lower leg is often an afterthought, usually relegated to a few bouncy sets of calf raises at the end of a workout. However, to fully develop all muscle groups in legs, you must understand the distinction between the gastrocnemius and the soleus.

The gastrocnemius is the diamond-shaped muscle visible when you flex your calf. It crosses the knee joint, meaning it is most active when the legs are straight. Standing calf raises target this area. The soleus lies underneath it and does not cross the knee. It is a workhorse muscle composed mostly of slow-twitch fibers. To target the soleus, the knee must be bent, which is why seated calf raises are essential.

There is also a muscle almost everyone ignores: the tibialis anterior. Located on the front of the shin, it is responsible for pulling your toes up toward your knees (dorsiflexion). If you suffer from shin splints or trip frequently when running, a weak tibialis is often the culprit. Tapping your toes or doing heel walks can strengthen this area, providing better balance to the lower leg structure.

Integrating Anatomy into Training

Knowing the anatomy should change how you program your workouts. A balanced routine isn't just about "feeling the burn." It is about biomechanical coverage. You need a knee-dominant compound movement (like a squat) for the quads and adductors. You need a hip-dominant movement (like a deadlift) for the hamstrings and glutes. You need isolation work for knee flexion (curls) and extension (leg extensions) to ensure the bi-articular muscles are fully stimulated.

Leg training is demanding because these muscle groups are large and require significant energy to repair. But when you train them with an understanding of their function rather than just their appearance, you build a foundation that supports everything else you do, inside and outside the gym.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the best exercise to hit all leg muscles at once?

The squat is widely considered the king of leg exercises because it engages the quads, glutes, hamstrings, and calves simultaneously. However, while it hits many areas, it doesn't maximize every muscle equally, so accessory work is still necessary for complete development.

Why do my hamstrings feel tight even after stretching?

Chronic tightness in the hamstrings is often a sign of weakness or pelvic tilt issues, not just a lack of flexibility. If your glutes are weak, your hamstrings overwork to stabilize the hip, causing them to remain in a semi-contracted, "tight" state to protect themselves.

Can I train calves every day?

Yes, the calves—specifically the soleus—are made of dense, slow-twitch muscle fibers designed for endurance and recover quickly. High-frequency training often yields better results for calves than treating them like larger muscle groups that need days of rest.